Practice Mars landings are teaching researchers how to work in space – Astronomy Magazine

Simulating the Mars environment

Planning a mission to Mars, even a simulated one, is no easy task.

First and foremost, the questions that guided the research were not simulated in any way: these were real questions asked about how microbes live in and interact with volcanic rocks.

I am a geobiologist and my expertise is in organic geochemistry. I want to know what microbes do in the environment and, importantly for astrobiology, what signs they leave behind. Within the BASALT program my research required that the samples were collected in a sterile manner, adding another complex layer to an already complex series of activities that must be done while facing the challenges of being in space.

Deviations from sampling protocols or not collecting enough contextual data about the sampling sites would have consequences for the validity of the results.

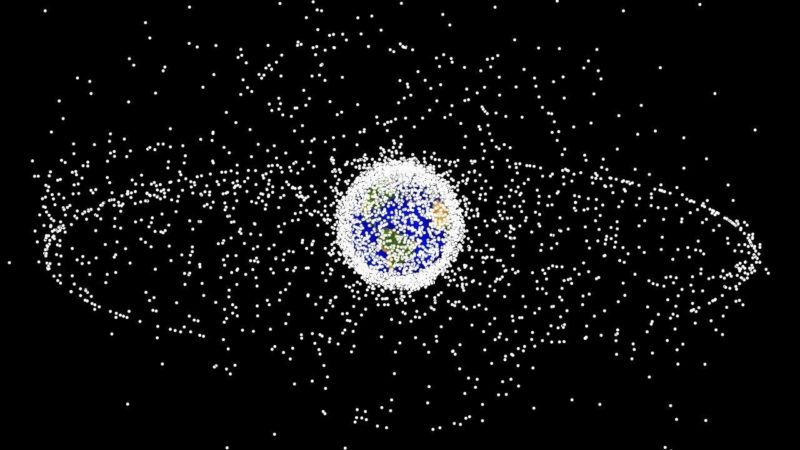

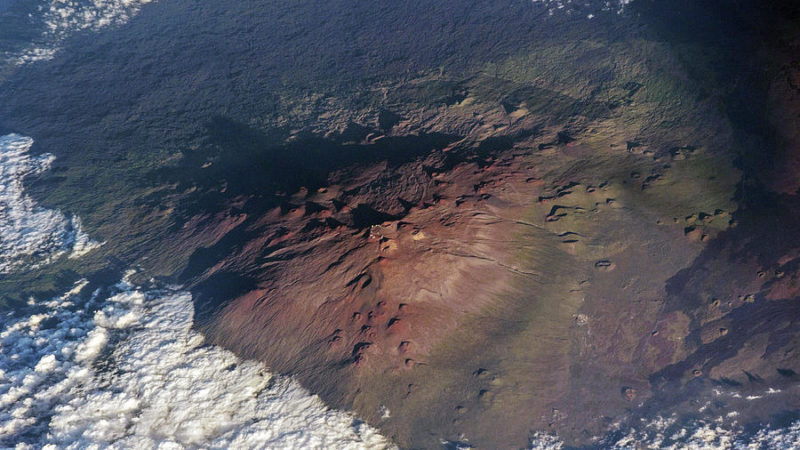

The BASALT team spent months planning the field deployments down to the last detail, including how many photos to take and estimating how long it might take to sample each rock. Individual sample sites in Idaho and Hawai’i were selected based on remote-sensing information available to the team (akin to using orbital satellite data to select landing locations on Mars).

At each site, people working on the surface (an extravehicular crew) gathered information and sent it to a crew in the who stayed in the space habitat (the intravehicular crew). Information gathered was then sent back to Earth. The intravehicular crew was the go-between, interacting in real-time with the extravehicular crew.

On Mars, once astronauts are on the ground, they would follow pre-planned traverses and search for basalt rocks that would be used by the scientists for research.

Communicating findings

A great deal of thought went into not only the type of data that the Mars crew would collect and send back to Earth for the scientists to examine, but also how they would then work with it and come to a decision about which rock they wanted the crew on Mars to sample. This could be affected by the conditions for communications including the bandwidth available: if low bandwidth conditions exist that limit transmission of data, could photos be used in place of high-resolution video? It’s like internet speed, if your connection is extremely slow you may rethink watching Netflix but you might still download those cat photos.

The BASALT program showed that it is possible to receive useful input from an Earth-based team over time delay. At the end of the program we learned quite a bit about how to effectively do this. For example, while video is helpful, high resolution photos are the preferred choice under bandwidth restrictions. Text, rather than voice communications were best for relaying important decisions between Earth and Mars. These and other results will be used to plan missions so that when we send humans to Mars we are doing the best possible job to answer fundamental questions about whether life ever existed there.![]()

Allyson Brady, Postdoctoral fellow, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.